Manual Therapy is a broad term used to describe a multitude of approaches and techniques where the clinician uses their hands to effect change in soft tissues and joints. The aim is generally to improve and/or restore mobility and motion.

The techniques and approaches vary considerably and clinicians often pursue a specialization to obtain mastery of a particular technique.

Manual therapy is well liked by clinicians and patients because of the hands-on nature of the interventions. It is used by Physical Therapists, Chiropractors, Occupational Therapists, Doctors of Osteopathy and others. Its effect has been demonstrated in many conditions, including low back pain, neck pain, disc degeneration, bursitis, trigger points, and many others.

Manipulation, Adjustment, Mobilization?

Many people think of bone-popping, joint-cracking thrust maneuvers when they think of manual therapy. While these maneuvers are definitely part of the manual therapy arsenal, they are but a small part of it. The therapist could be using very gentle manual pressure to coax a muscle into relaxation or apply stronger pressure to stretch some stiff tissue after a joint has been immobilized for a while.

The following are some specific techniques that are performed at this clinic.

Spinal Decompression

commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29987032

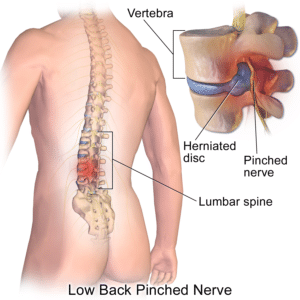

Decompression is an approach aiming to decrease or relieve pressure inside a intervertebral disc in the spine.

When a disc gets injured, it may start bulging to the outside, which can then put pressure on the surrounding tissues. This will cause pain, muscle tension or spasm, nerve pain and possibly symptoms radiating into the arm or leg. Therapy aims to encourage the disc to reabsorb the bulging nucleus but it is often hard to do. Decompression helps.

With decompression the therapist applies manual traction to the lower part of the spine while the upper part of the spine is fixed to the table. In other words, the spine is being pulled apart a little. This causes a decrease of pressure on the inside of the bulging disc, thus helping the disc to heal.

The approach is best performed when the manual intervention is assisted by advanced mechanical traction devices. These devices mimic the hands of therapist, gradually applying traction and then releasing it, repeating that multiple times over a period of 30 minutes or so. The advantage of using mechanical devices to complement the manual intervention is the precision and reliability of the traction. The device can be programmed to deliver exactly what the patient needs for exactly the right amount of time and do so reliably and consistently every single time.

Myofascial Release after Head and Neck Cancer

The body has many layers of connective tissue throughout the body that provide it with structure and form. These structures are called the fasciae. Imagine thin sheets of woven tissue separating the different structures in the body – muscles, joints, organs, etc. – while at the same time allowing the whole body to move without restriction. Some people compare the fascia to a close-fitting, body-hugging sweater – it keeps the body warm but the wearer hardly notices it because it is so light and it moves in sync with the body. This comparison is a good one as it illustrates what might happen with injury. Imagine that sweater getting torn. It is so delicately made that fixing it with thread and needle will almost certainly not make it come back to its original silkiness and smoothness. In fact, there will probably be some structural weakness there where the fix is.

So it is with the fasciae in our body – when they get hurt, impaired movement often results. Muscles can’t move properly because the fascia within which they are contained is not as flexible as it once was. This is especially true with patients receiving radiation because of head and neck cancer. The radiation changes the genetic makeup of all the tissues in the radiation beam and causes them to lose flexibility. They become like scars.

Myofascial Release is a technique where the therapist uses his hands and other tools to restores some of this flexibility. In the case of the neck, the patient will be asked to lie or sit in a stretched position and the therapist will then manually stretch out the stiffened tissue. The technique can not repair the damage that was done but movement can be increased and thus function improved. In the case of the head and neck cancer patient after radiation, this may often translate into a better voice and better swallow function.

Myofascial Release is a technique where the therapist uses his hands and other tools to restores some of this flexibility. In the case of the neck, the patient will be asked to lie or sit in a stretched position and the therapist will then manually stretch out the stiffened tissue. The technique can not repair the damage that was done but movement can be increased and thus function improved. In the case of the head and neck cancer patient after radiation, this may often translate into a better voice and better swallow function.

Myofascial Release to the head and neck area is usually accompanied by other treatment interventions to maximize the benefit. These may include electrical stimulation of the muscles (NMES or VitalStim Therapy), surface EMG biofeedback, ultrasound, and of course exercise therapy.

Limitations

While Manual Therapy is used for most conditions treated at this clinic, it is almost never the only approach that is used. Other interventions may include exercise, postural correction, advanced therapeutic modalities such as shortwave diathermy, electrical stimulation and biofeedback.

The skillful combination of these interventions – a so-called multi-modal approach – is what makes the overall therapy so effective.

References

Ajimsha, M. S. “Effectiveness of direct vs indirect technique myofascial release in the management of tension-type headache.” Journal of bodywork and movement therapies15.4 (2011): 431-435.

Fredin, Ken, and Håvard Lorås. “Manual therapy, exercise therapy or combined treatment in the management of adult neck pain–A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 31 (2017): 62-71.

Ghodrati, Maryam, et al. “The Effect of Combination Therapy; Manual Therapy and Exercise, in Patients With Non-Specific Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” Physical Treatments-Specific Physical Therapy Journal 7.2 (2017): 0-0.

Yaseen, Khalid, et al. “The effectiveness of manual therapy in treating cervicogenic dizziness: a systematic review.” Journal of physical therapy science 30.1 (2018): 96-102.